The Adventurer, Conqueror, King System, short ACKS, is essentially “just another B/X clone”, (or more accurately: BECMI-clone?) albeit with some unique highlights.

For one, it is more insistent on driving towards Domain play, hiring armies and confronting opponents on a grander scale than any other game to my knowledge. The goal is to rule the land and lord over lesser domain holders.

For another, it attempts to bring economic sense into the fiscal madness that is the D&D monetary system.

As a minor additional point: It has a maximum level (generally 14), where further growth is no longer in the cards: If you are already the top-honcho, you can only keep growing in worldly possessions and earthly power, by amassing gold and ruling over more lands. No more hit points for more gold.

First Brush

My first brush with ACKS was when someone told me that it was fantastic and great, and so I went and checked it out. I saw two things I did not like:

A greater number of classes (I am in favour of very few classes, because I believe that fewer classes inherently push players to develop individual characters in play, while having dozens of classes promotes a mindset that class = identity),

and many, many rules. It just felt like a lot and not simple at all, and since I prefer actual play over theoretical work that did not seem so attractive at the time.

Looking at the domains at war rules (in my quest to find the perfect mass battle system – one that integrates seamlessly with personal-level play in multiple systems) I found them similarly convoluted and difficult, at least at my first skim.

So I gave up on it.

Too soon?

Tangential awareness

Following that I was low-key aware of the continued existence of ACKS, mainly due to regular mentions of the system by fans, and regular comments about the system (mainly positive), and also through second-hand anecdotes about its fans and its creator (mainly negative) in the wider hobby-conversation. (I did not have any conscious contact with that community myself, so this is basically rolling on rumor tables.)

Ultimately I never saw any original-source-content to back up the negative comments. When I did witness Macris in person, as a guest on some Podcast or Video, he came across as polite, soft-spoken, and constructive.

His fans were very dedicated, but I never saw them attack anyone. Rather, I saw them getting attacked.

But honestly I did not pay very much attention, because I had discarded ACKS back then and focused on other games.

Fresh motivation

Now, why did I return to ACKS?

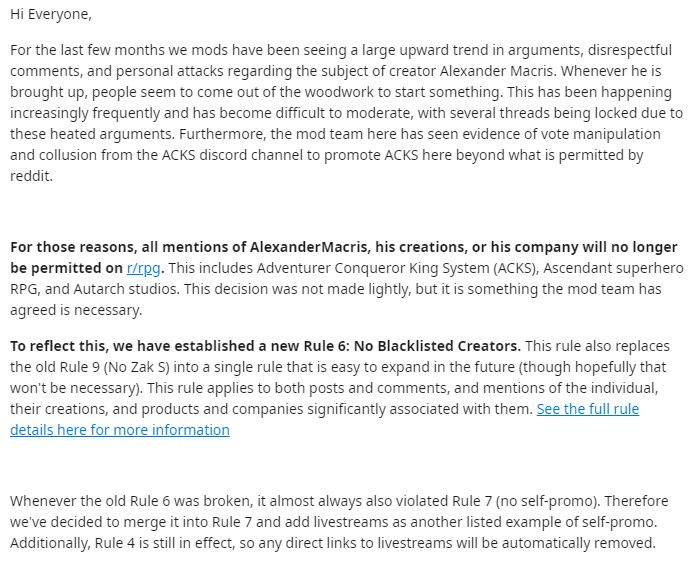

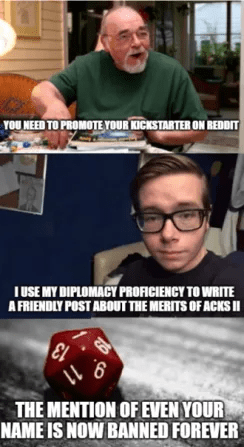

That was because mention of the system, its creator, and its new Kickstarter campaign for ACKS II, the Imperial Edition, have been banned on some popular sub-reddits.

This rather bold move was explained to be a reaction to an allegedly rule-breaking campaign by fanatic cohorts of the ACKS-fans; although I was unable to find any such a campaign.

Weird, huh?

The move got me thinking, though. If there is such a strong reaction to ACKS II that they must ban even its name … there can be only two explanations.

Either ACKS-fans are actually invading that subreddit with vile cohorts of doom,

or the system is exceptionally good and everyone is afraid it will dominate.

How to find out?

Naturally I looked for the vile cohorts doing vile things first. Searches turned up nothing. ACKS II-mentions still in evidence on Reddit were fine and normal. Were all the vile things deleted by mods?

To explore this theory, I joined the Autarch subreddit, which continues to exist parallel to the Anti-Autarch spaces, and the Discord.

The ban did not feature on the former, but was discussed on the Autarch Discord, albeit only in a calm manner, resigned to such measures as if they were a natural weather phenomenon. There was only this funny meme made about the incident:

No vile cohorts spotted, just a nice way to react to adversity.

Validity of the ban: Not confirmed.

Onward to test explanation 2: Does that mean the system is so good it has to be buried by its competitors?

ACKS I

Hard to tell about ACKS II yet, fresh as it is.

So I start with a look at the game’s earlier iteration: ACKS First Edition.

As a high-level overview it is, as mentioned, close to B/X, the Basic D&D version of Tom Moldvay/Dave Cook/Steve Marsh, or, given that we also have banded armor and skills in it, maybe even closer to BECMI of Frank Mentzer. You have your classic Attributes, called Abilities, you have hit points and Hit Dice, an Armor Class and XP. Bonuses and penalties are just like in Basic D&D. You have prime requisites and get +5% XP if you have the attribute at 13 or better, +10% if you have 16 or better.

Classes

On the second read, it does not have that many classes after all. I was probably in a very allergic phase when I looked at the book for the first time.

There are “core classes”, which are your standard human classes down to the XP-thresholds. Then you have so-called “campaign classes” on top: Assassin, Bard, Bladedancer, and a number of classes for Dwarves and Elves which are called “Demi-Human classes”.

(I hate the word “demi-human”, but that’s just my personal taste. When playing a dwarf I regularly call humans “demi-dwarves” to make them see why it is weird.)

Fighter

The Fighter has a damage bonus for missile and melee both.

AC is ascending.

A Fighter has a to-hit number of 10+ at level 1. That is a bit like a target number. Armor adds to that, so Leather Armor is a plus 2 and makes that 12. Rolling a 12 or higher hits.

Let us quickly compare that to B/X and Descending Armor Class, which I am more used to by now: A Fighter has a Thac0 of 19. Leather is AC 7. We reduce 19 by 7 and get to 12. Same, same.

But I know most people find Thac0 too difficult and prefer AAC, so let’s regard this choice benevolently.

Thief Skills

The Thief differs from B/X in that he has no percentage-skills but uses a d20.

How do they translate to “normal” B/X?

At level 2, a thief opens locks with a chance of 20% to open a lock. That’s 4 numbers on a d20. Same, same. But actually, makes sense, because why take a d% if you have the d20 already in hand? Hear noise at 14+ is a 35% chance. Roughly a third. That’s much like the 2-in-6 chance of B/X. Climb walls is where things are different: Thieves usually start with super-high values like 87% off the bat. The only skill they are really worth a damn. In ACKS they start with a 6+, so no, they are nerfed. Poor thieves.

Henchmen

Right from the start ACKS suggests you hire help. Makes sense, since that’s the object of the game: Not “Become a superhero.” Become a boss.

I like that, because Hirelings and Retainers are such a wonderful part of the game in my opinion. I miss that aspect a lot in more modern systems and with modern-minded GMs who are not used to it or actively discourage hiring.

Equipment

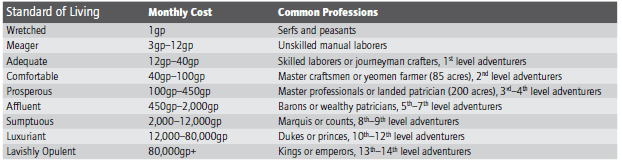

Still, so far no revolutionary stuff. Chapter 3 is where ACKS is supposed to shine, if sources can be trusted: Equipment, money, budget. Classic D&D has horrible economics that make no sense whatsoever. Lamentations of the Flame Princess works to iron out these kinks, and Swords & Wizardry does great work in providing more sensible living wages for hirelings than the original source material. So, how does ACKS shape up?

Serf living is what we pay our spearmen in standard D&D. Small wonder they don’t want to go into dungeons with us. A sword costs 10 gold pieces: A month’s expenses for a random normie. Leather armor is 20 gold pieces. Armor and weaponry are an investment. A javelin is 1 gp, a spear is 3 gp. That’s sensible.

Now, what about food?

Rations in ACKS are seriously cheaper than in B/X. 3 silver to 3 gold, depending on quality, for a week. That vibes with the meager earnings of unskilled labour. So yes! The people who have, long ago, pointed me to ACKS when I complained about the wonky economics of B/X and OD&D – they were right all along.

And my favourite gripe, the bow:

I often argue that it is silly to pay 40 gold pieces for a longbow, but 5 gold pieces a month for an archer. In ACKS we pay 7 gp for the longbow. This makes sense. 6 torches are 1 silver piece. Works for what is essentially just a log of wood with some tar applied. Rather than a gold piece – the living expenses of a poor wretch for a whole month.

Good, named and statted henchmen who come with you into the dungeon, they get their own monthly fee, starting with 12 gold for a level zero nobody with the guts to face monsters, and 50 gold per month for a level 2 chad. Plus whatever treasure share you negotiate.

Encumbrance

Here I stumble: The weight of things is given in “stone”, which is completely alien to a continental like me. Luckily, ACKS is merciful and rounds “1 stone” down to 10 pounds. Normally it would be 14 pounds, or 6 kilograms, which would lead to a bookkeeping nightmare. A rough “10 pounds / 5 kilos” I can handle.

More easy encumbrance: 1 AC = 1 stone.

6 items are 1 stone. (where 12 spikes or 20 arrows are each as a bundle 1 item)

1 heavy item is 1 stone.

1000 coins are 1 stone.

My old algebra teacher would suffer a heart attack, but at a gaming table this sort of spittle times thumb arithmetics are feasible.

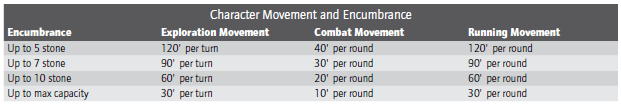

So how do these “stone” weigh us down?

Fine system.

Proficiencies

Now we venture away from B/X territory: Skills and proficiencies. Such don’t exist in Moldvay’s basic, they are abstracted from attributes or rolled with a d6, depending on how the GM, well, rolls.

That pun just happened all by itself.

Well, ACKS has specific proficiency lists for the various classes. Characters start with one of them (or more if high INT). More proficiencies can be added at level 5, 9, and 13.

I’m not fond of that needless extra complexity, although they don’t overdo it. Proficiencies like “Combat Trickery” that allow a character to “force back” or “disarm” an opponent, exist, but they do not suggest that other characters can NOT force back or disarm an opponent – they only make it easier for those who have the, so to speak, feat.

It is not the worst skill system, or to be completely honest, for a skill system it is pretty good. I can live with it.

On the real plus side, there is something called “Craft”, which is actually a good, useful skill, like loving parents would want a little adventurer to learn. So if you have that and lose a leg in the dungeon you can still be a productive member of society and a valuable contact for your old buddies.

Magic

Here ACKS veers right off the well-trodden D&D road. Even though it keeps the classic duality of Divine and Arcane spells, it throws the whole Jack Vance system out the window. Instead, the system goes the more popular way and allows magic users to cast a certain number of spells from their known repertoire.

Eight hours of uninterrupted sleep recharge the spell slots.

As they advance in level, arcane spellcasters can add new spells

to their repertoire in a few different ways. All mages and elven

spellswords are assumed to be members of the local mages’

guild, or apprenticed to a higher level NPC. When they gain a

level of experience, they may return to their masters and be out

of play for one game week per spell while they are adding new

spells to their repertoire. Their masters will teach them spells

equal to the number and level of spells the caster can use in a

single day. Characters of 9th level or above do not have masters

to teach them spells, so they must find or research them. When

a master is not available, mages and elven spellswords depend

entirely on finding spell scrolls, finding other spell books with

new spells in them, or conducting spell research.

The game easily explains with a pretty beautiful paragraph why magic is such a highly specialised work that takes up a lot of time and bars wizards from training with swords and bows in their down time.

For an arcane spellcaster to have a spell in his repertoire, he

must keep track of complex astrological movements and star

signs that are constantly changing; he must daily appease

various ghosts and spirits that power certain dweomers; he must

remember and obey special taboos that each spell dictates. All

of these strictures, and they are many, can vary with the season,

the lunar cycle, the caster’s location, and more. Having a spell

in the repertoire is thus an ongoing effort, like maintaining a

friendship or remembering a song. Mages may collect spell

formula from many sources, but only the most intelligent and

learned arcane spellcasters can maintain a repertoire of more

than a few spells at a time.

I like that.

I also like ritual spells which can be used at level 11 or higher to shake the foundations of reality itself, but they take time, funds, more time, and a workshop, but allow the production of magical items. Given the high level of the creators, scrolls and potions don’t come cheap. 500 gold pieces are suggested for a healing potion, which puts them right out of a poor working man’s plane of existence.

Campaign Play

Magical research can be undertaken once a caster reaches level 5, and requires the throw of a d20 to determine success, which gets easier at higher levels. Forcing open a door we see the d20 roll again. The same is true for a cleric’s Turn Undead and Evasion throws for running away. Clearly, Macris favours this die above all others. Although, the surprise roll is a d6, and the reaction roll 2d6, just like back in the days of yore.

For some arcane reason the system puts in the energy to clearly distinguish between rolls and throws of the dice in different situations, even though it still comes down to casting a die. If there is a range of possible outcomes, it calls it a roll, if there is only success or failure, it names it throw. Mechanically though, it is all the same. Funny.

Charging allows triple combat movement rate, lends +2 to hit and gives a -2 penalty on AC. Double damage – all very classic.

Damage is handled not unlike Lamentations: Tiny weapons do 1d4, small weapons 1d6, medium weapons 1d6 or 1d8 depending on use, and two-handers do 1d10 with an initiative-malus of 1. Dropping to zero Hit Points forces a roll on a Mortal Wounds table to find out what happens to the victim.

An interesting variation on the classic “cleaving” debate: “Whenever a combatant kills or incapacitates an opponent, he may immediately make another attack throw against another opponent within 5 feet.”

Note: “A combatant”. There is no mention of level, only of movement range. Isn’t that interesting?

And finally,

Domains & More

Strongholds are much like in B/X, but with variable income rules per district rather than the flat taxes from D&D, and with an obligation on high level clerics to actually tend the flock. Ignore the faithful and they will lose heart and leave. Buying civilized land is prohibitively expensive, so the motivation to secure a piece of wilderness and drive out the wyverns and cockatrices is clear. Also expensive, though: To build a castle out in the wild is no mean feat. And even then, population can shrink (and taxes dwindle) or grow (and income bloom).

Domains also have a moral score, which represents how content or unhappy the population is. Ruling a domain in ACKS is a real job that demands attention. Make sure your subjects are thriving and have fun, and you prosper.

There is even something about crime and punishment, with friendly, standard, and drakonian laws, depending on the local lord.

This makes me think about the situation from a game in a different system where I am player. A fellow player has acquired a castle, cleaned and repaired it, and wishes to develop and populate it and the land, make the area prosper. But the rules don’t cover that, and neither do the other players have an interest in playing such “boring” stuff out. So his designs are frustrated.

These rules here would have been exactly what the GM needed to give the player something tangible to work with between sessions.

To round it off, there is also an mercantile system for those who want to build a trading empire and leave the subjugating of lands and monsters to others. The rules even allow to gather experience and level up due to trading and profits. I wonder how that would play out: A party of adventurers with a good friend who levels up through business ventures. The good friend could sell magical items on various markets, while the party could help with serious problems haunting their friend’s caravans and ships.

Conclusion, and a turn toward ACKS II:

A good system. A lot of thinking went into this, and the result speaks for itself. Yes, it is a lot of words, and it could be easier to digest. But the actual game content convinces.

Which makes me all the more interested in the current finishing touches for ACKS II, the object of the banhammer. The playtest rules are out, the system is supposed to stay very close, and compatible, to ACKS I, only refining it and incorporating well-loved additions like mass combat rules and other goodies.

True, false? More to investigate.

Let’s see if an opportunity to test ACKS II presents itself – after I carve out the time to explore the new rule document in written form and find out how much, and where, it differs from the predecessor.