The Old Lords of Wonder and Ruin is a retroclone, but not one of D&D. This short booklet attempts to make the old Wargame – Chainmail – and its procedures clearer and more concise for the modern reader, while staying as close to the source material as possible. The Author’s name, “Alchemical Raker”, is unfamiliar to me, but he lists a number of well-known names for consultation and rules research.

Chainmail – what is it?

Just in case you, dear reader, don’t know: When Dungeons & Dragons was fresh and new, the combat rolls with a d20, now so classic as to be the go-to- way to fight, were called an “Alternative Combat System”. Chainmail procedures were suggested as the normal one: Chainmail rules predate D&D and focus mainly on battlefield moves, but also have a Man-vs-Man and a Fantasy Combat section to pit human fighters against various monster types. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson didn’t even think to include any sort of hints about them in the 3 LBB, probably because they expected everyone to have them anyway … which may be a decisive factor in making the “Alternative Combat System” the future standard.

Why would we need a Retroclone of that?

Many players are struggling with mass battles, which may be a big factor in why they hardly ever happen in most games, and why there are so many wildly different systems out there to handle them at those rare times when there is no way around them.

Many of those try to take some pointers from Chainmail, despite the fact that there existed, and exist, quite different rules systems for mass combat – I assume that is, for one, because D&D made Chainmail great and famous, and for another, because many Conflict Simulations are often very narrow affairs about a particular conflict (like Napoleon’s battles), whereas a mass combat system for Roleplaying Games needs to be flexible if it wants to adapt to many different game worlds and incorporate wizards and fantasy races and their specialites.

The Old Lords of Wonder and Ruin stay pretty close, very close, to the Chainmail framework. There are some small differences in the order of the topics, and it is a bit more explanatory: Gary Gygax, in his early work, generally assumes familiarity with the genre and his examples do the same.

Obviously!

There was no way to know his stuff would be the success story it was. It was logical to assume it would only find readers in the existing nerdy circles of the wargaming community, and it was also logical to assume it would hardly earn back its production cost, if that. So no reason to make it super accessible.

Is The Old Lords of Wonder and Ruin super accessible?

Define super. Let us say No.

Like Chainmail, it also assumes some sort of familiarity with the genre, and rightly so. Let’s not kid ourselves, this will remain a niche product. But it is clearly easier to grasp and to learn from.

Yet true understanding needs practical application.

Into the nit and gritty

Checking the details of the rules we find that no great surprises await. It is, as advertised and expected, an extremely faithful retelling of Chainmail – although with much different phrasing, for the purpose of clarity of voice and clean visual presentation.

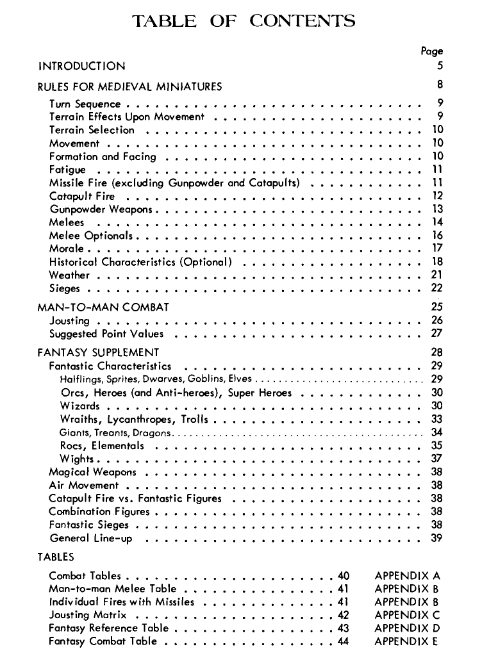

The table of content reveals the many similarities but also some slight re-ordering.

Compare the one for Chainmail with the one for Old Lords:

Content- and rules-wise, if you know Chainmail, you also know The Old Lords of Wonder and Ruin. So good job, Raker. Some care has been taken to explain particularly difficult elements of the game, like the numerical difference between a Superhero and a Hero in terms of the Multiattack rules (for example, Fights as 4 Men +1),

or the yardstick to find out where a cannonball hits and what units it will knock out.

So, the Yardstick

Zooming in, this is what Chainmail has to say about it:

.

And this is the description in Old Lords:

FC

There are changes to some of the stats (for example, an ogre has a fighting capability of 6 men in OLWR, rather than the 4 men of Chainmail). Which makes a bloody (literally bloody!) difference if your proud little band of 200 horsemen happens upon 18 ogres in formation.

Plus & Minus

Wording-wise, the function of modifiers to die-rolls have been reversed: a flanking maneuver will not yield +1 on the dice roll, but rather -1 on the target number. Which is arithmetically the exact same thing, but the wording is unusual and therefore more the mark of a deliberate thought rather than a simple rewrite.

What may be the reason? It sure is a differentiator in legal matters, which may play a certain role, but mostly it move a calculating operator from one end of the equation to the other, which may be a simple question of personal taste.

Morale

One of the trickiest, and yet one of the most important aspects of any mass battle game, is Morale.

Why is it important? Because Morale can break an army and let a numerically weaker opponent win, and it can decide a battle surprisingly early. Excluding Morale makes sense for highly stylized battle games like chess, where the hopes and dreams of individual soldiers appear quite unnecessary.

But why is it tricky? Read here:

.

Now roughly the same content in Old Lords of Wonder and Ruin:

It is a challenge, but clearly it will get easier if done often. And often it needs to be done, in Chainmail as well as in The Old Lords of Wonder and Ruin.

And as a last tidbit:

The Weather.

Chainmail:

.

The Old Lords of Wonder and Ruin:

Almost exactly the same.

All these examples show that the content is very faithful to the original, maybe unparalleled so, but showcases the changes in design that are intended to make the retroclone easier to read and understand.

Hands-On Examples

Throughout the rules, there are various examples of play, some more helpful than others, which in any case go a ways to illuminate the meaning of rules. Everything is easier to understand when it is not just numbers, but Jimmy the Example-Veteran battling an orc. Or 26 orcs overrunning 10 heavy foot.

Despite this more detailed approach, the overall page-count does not exceed that of Chainmail – nay, it reduces it! An impressive feat given that Old Lords includes these examples and even goes so far as to clarify some instances of obscurity (like Lycanthropes being killed on 4 to 6 simultaneous hits – which Old Lords explains as four for Werewolves and six for werebears).

Sometimes the rules do differ in meaningful ways. Take, for example, an unhorsed knight. When he hits the ground, both rules sets will ask you to roll a d6, and the outcome will be mostly the same, but on a roll of a 6, in Old Lords the knight will be stunned for two turns, whereas in Chainmail he will be stunned for three.

The aforementioned Lycanthrope can only be hurt at all if assailed with magical weapons –

Aesthetics

- The font is easier on the eyes. Not surprising, again; groans about the typeface used in the original rules are common, it is preferred only by the most diehard purists.

- Old Lords makes use of finer Art

- And it is ordered better, listing spells by power level rather than alphabet, and armor as intuition would suggest (armor, then armor + shield) rather than the way it was done in Chainmail (sometimes so, sometimes differently).

- On the downside, it uses more fonts than it should, which is likely to raise the hackles of professional graphics designers.

Tips

Instead of Chainmail’s Introduction and Foreword, Old Lords of Wonder and Ruin includes some general tips about campaign play and setup near the end, including a confirmation that it is, indeed, a new form of the original mass battle rules associated with D&D, and some explanation about the spirit of the game weighing heavier than the exact wording. A stance I agree with, although I know a good number of gamers would hate that talk – those who have spent months deliberating over particular positions or absences of commas, arguing fervently that there are no typos, only very carefully codified insights of titanic import.

As an extra that is not present in Chainmail (how could it, given the Chronology?), Old Lords of Wonder and Ruin takes a moment to explain how the rules can seamlessly integrate with an RPG and can be adapted to various sizes from 100 or 20 men for a figure down to just 1 man versus another, and it explains Braunstein campaigns of warring polities led by players vying for political power.

Following next: A test-run of Old Lords.